How I do strategic planning for life

In my 20s it didn’t appear that my life needed much planning. Like many young, educated professionals, it appeared that my career had a momentum of its own: opportunities presented themselves and I either took advantage of them, or declined. The goal was simply up: more money, higher job titles.

I had a loose idea of what direction I wanted to head, and when certain forks in the road of life arrived I made my choice and continued on. It all seemed to be going well. At 29, I was director of communications for an internationally recognized climate think tank based in Washington, D.C. My office in Dupont Circle overlooked the entire Northwest part of the city, and in the distance, I could gaze on the National Cathedral, a gorgeously imposing work of Neo-Gothic architecture that declared to me: I had arrived.

And then, everything crashed.

First, it was my relationship. I was a new father to a perfect one-year-old boy, but the relationship with his mother had never really worked. It unravelled over the course of a year, punctuated by brutally painful, soul-destroying fights.

In the middle of all that, the climate think tank laid me off. Its finances had been declining for a decade due to some unspecified combination of benign neglect and poor financial planning. In any case, the communications and marketing people are always the first to go under such circumstances.

The prerequisites for strategic life planning (Or, what to do when you’re a single parent and jobless)

This might go without saying, but it’s near impossible to be deliberate about planning your life when you are a single parent without a job and no savings.

Strategic planning for life isn’t something I would ever have the audacity to recommend for someone in this situation. My only recommendation would be the obvious one: go get a job. Any job. Get stable, financially.

Which is what I did. I called an old colleague who had started a boutique marketing agency, and I asked if he had any work. As it turned out, he was launching a rebrand for one of his clients and needed someone to handle the social media channels. He sub-contracted the work to me, and I had my first client.

In time, I got more clients, and in some more time I was able to breathe long enough to think about the other things in my life other than money. It took a few years, but the lesson I learned from that time was this: when you have kids and are stressed about money, nothing else matters that much.

Thinking back on it, I simply embodied one of the great facts of being a new parent: my dreams of a different path were on hold until a later date. A few years later, that date finally came.

My first strategic plan

My largest client in 2013 was an emergency physicians group. I was increasingly integrated into their business, and I was invited to the company’s annual strategic planning retreat.

Emergency physicians are trained to think on their feet, lead a team, and handle anything that comes through the doors of the ER, whether it’s multiple gunshot wounds or a baby with a fever. One thing they are not trained in is long-term strategic planning.

That said, the doctors who led this particular group had gone to extraordinary and fairly effective lengths to train themselves as managers and business leaders. They had a pretty good process for strategic business planning, and it went like this:

Each year, the group’s senior partners created four broad goals for the next year. They never went beyond one year because their industry was changing too fast to make any meaningful goal beyond that year.

At the retreat, a wider group of senior leaders divided themselves into four groups according to their interest in each of the goals. These sub-groups came up with a plan for achieving the goals, as well as quarterly milestones for each of the initiatives.

At the end of the year, each group reported back with a simple “red/green” - green if they achieved the goal; red if they didn’t. Reporting back in this way forced the company to articulate goals in such a way so that there was no room for ambiguity. Goals had to be expressed in such a way so that it was clear: either they had achieved it, or they hadn’t.

A few months later, I decided to adopt parts of this framework for my own life. First of all, I liked the short time frame. One year seemed long enough to achieve something substantial, but not so long that changes in my life could derail the original intention.

Second, I appreciated the simplicity of declaring a goal either red or green and of having to phrase my goals in straightforward, unambiguous language.

On my birthday that year (which incidentally comes a few days before the New Year), I parked myself in a coffee shop and outlined my goals for the next year. I created a Google Doc, and declared at the top of it that at the end of the year I would take a red or a green for each of the goals. I divided the goals into three categories - creative, financial, personal/social - and added quarterly deadlines and milestones.

Here’s what the top level “Creative” section looked like at the end of the year:

In the span of the next 12 months, I succeeded in:

Training myself how to use Premiere Pro

Writing a 10,000 word short story and submitting it to 20 journals for publication

Writing a 120-page feature length screenplay about Ferdinand Magellan

Directing my first short film (18 minute run time) and submitting it to festivals

It was, without a doubt, the most productive year for my creative goals that I had ever had in my life.

I also completed most of my financial goals that year, although I took a red on fully paying off my student loans (that would come the following year).

In the “social/personal” category, meanwhile, I failed to meet any of my goals. One of the major ones in that category had been to find a personal or professional group to join in order to expand my circle of friends. It never happened (thus presaging a years-long struggle to develop close friendships in the D.C. area).

Still, I considered my first year in “Strategic Planning for Life” to be a wild success.

Learning how to drop goals

One of the major lessons I learned in the first few years of going through this process was how to drop goals. Each year on my birthday, I would again sequester myself in a coffee shop to plan for the coming year. But I would also look back on the achievements - and failures - of the year behind.

I realized that in addition to creating a system for achieving life goals, I had also stumbled upon a system for dropping them. After all, the “reds” that I took weren’t just failures; they were indications that I was not fully committed to that project.

As I looked through what “reds” I had taken at the end of each year, I decided to carry a few of them over to the coming year, and altered my approach and milestones appropriately. But the large majority of them I simply dropped from my list, having learned a little more about myself and what I truly valued.

Not only had the process led me to achievements beyond anything I had expected, it had also become a testing ground, a way for my ambitions to sort the wheat the from chaff, so that I could learn what to leave behind and what to continue on with.

Time well spent

For four years, my annual strategic planning session had become somewhat of a ritual. Before that I had always approached my birthdays with some degree of dread: another year passed, another year older, and still without having achieved any of the things I wanted to in life.

But the strategic planning had made my birthdays into something a bit different: a way to mark what I had achieved that year - and the achievements were many. In 2017, I wrote and directed a feature film, a gigantic undertaking and the realization of a life-long childhood dream. I was proud and still am.

Still, I realized I needed to make a change to the way I thought about my life. This was in part motivated by the Time Well Spent movement (founded by Tristan Harris, who has since created the Center for Humane Technology). What Harris crystalized, for me, was something that had already been germinating inside me for a while: the most important decision in life that we make each day is how we spend our time.

Time is everything. It is our most precious resource as humans. It gets spent whether we spend it deliberately or not, and once gone we never get it back.

Most of us spend our time without ever thinking about the choices we make along the way. The most important decision we make about time is almost always related to our work and our career, since work and career is where we spend most of our waking hours.

But I didn’t want to spend this precious resource of my time doing work that I didn’t like or didn’t care about. I wanted to spend as much time as possible doing the things that I did care about, which meant: I had to figure out what I cared about.

A major evolution to my strategic planning: incorporating values

At the end of 2017, I made a major change to my process. As usual, I loaded up last year’s Google Doc and took my reds and my greens. But when I began the document for next year, I added a new section to the top of it: values.

Here’s that list:

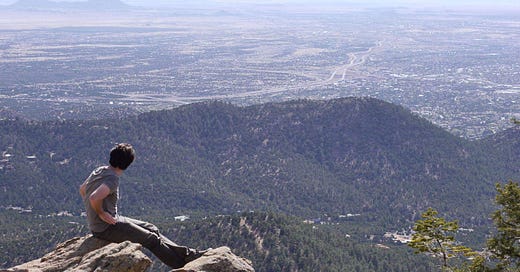

Time outdoors

Time with friends & family

Continuous learning

Creative endeavor

This is how I wanted to spend my time: outdoors, with friends and family, and pursuing continuous learning and creative endeavors.

In the next section, I revised my goal categories. Instead of three categories labeled “creative, financial, and personal/social,” I created goals tied to four categories, one for each of the values.

Under time outdoors, I committed to specific amounts of time spent rock climbing and kitesurfing. Under time with friends and family, I committed to specific amounts of time spent sharing a roof with them (that Summer, I rented a house in Galicia and invited my family to join; it was a glorious month on the Spanish coast).

And so on.

Adding those values forced me to clarify the why. Perhaps I needed those few years of simply focusing on the achievements themselves, of racking up wins after having put off for so long simply making the attempt. But at 36, I was truly beginning to feel the march of time with a vividness I hadn’t experienced before.

I needed to make sure that as this precious resource ticked ever away, that I at least observed it do so with intention.

The 5/25 rule

Later that year, I came across a story about Warren Buffet. The story goes that one day Buffett had a conversation with his pilot, who had been working for him for ten years.

Buffet joked that the fact that the pilot had been working for him for so long was a sign that Buffet wasn’t doing his job. The pilot needed to direct his own path and move on. To help, Buffet asked the pilot to list his top 25 life goals, which the pilot assiduously proceeded to do.

Then, when the pilot had the list, Buffet told him to circle his top five. Then, Buffet asked what the pilot planned to do with the other 20, and the pilot responded that they were all still very important, but secondary. He would focus on the top five, but he would also keep the other twenty in mind as he thought about where to focus his time.

But Buffet explained to him that he had it wrong: the other 20 were the “Avoid at All Costs” list. No matter what, the pilot was to ignore them and focus only on the top five. Only then would he have the clarity needed to achieve what he wanted to in life.

How I integrated values and goals, both short- and long-term

For a few weeks, I was obsessed with Buffet’s 5/25 rule. I made the list of 25 myself, and then struggled and struggled to select a top five. Each time I thought I’d had it narrowed down, I would wake up the next day and revise the selections.

I spoke about my list with my family, and I asked them for input and advice. After a few weeks, I thought I had settled on a top five, but I still proceeded with a certain unease.

For years, I had been focusing only on the year ahead, and with great success. This was the first time I had actually written down goals beyond that time horizon, and they were life goals at that. I felt in over my head, overwhelmed, even a bit paralyzed.

I was prepared to think more long term about what I wanted to achieve in life, but at the same time the enormity of the project conflicted with the limited scope of the strategic planning process I had already been using with such success.

Today, the 25 priorities are in a spreadsheet in my Google Drive, with the five I’ve selected as my top priority shaded in yellow, for in progress. Over the past year, I’ve accomplished two of them - those are now shaded in green, signaling complete.

Meanwhile, when it came to my annual ritual at the end of last year, I used the five in yellow as a rough guide to articulating my narrower annual goals, which are still grouped according to values. In this way I’ve melded the two methods together: a list of annual goals according to values, but with specific achievements chosen according to priorities chosen from the list of 25.

Conclusion

The only problem with this approach is this: every once in a while (but certainly more often than we’re ever truly prepared for), life throws you curveballs.

For me, it was losing my job earlier this year. All of a sudden, I had far less money than I could count on in the future. On the other hand, I had far more time.

This led to a re-evaluation of both my short- and long-term goals. Fortunately, I had done the work. I knew what my values were, how I wanted to spend my time, and what I wanted to achieve. And as the shock of the job loss began to wear off, I realized I could actually achieve far more of what I wanted to over the coming year than I could have with the job.

Suddenly, my desire for travel and learning, and other goals which I thought were years away were suddenly all within reach. I had the money in savings - I had been wise, that way. What I hadn’t had was the time and the freedom. Now, I did.

Even the search for a new job (or, more accurately: any method of earning the money I needed which would best support my life goals) had guideposts to it in terms of what I valued and what was important to me, and those guideposts were far away indeed from the mile markers of my 20s, which had read simply “more money” and “higher job titles.”

That is what I wish for everyone, really: a life that transcends the base societal expectations of ever-greater wealth and ever-greater status; a means of work or money that supports their life, and not the other way around; and time on this earth that is well spent according to how they wish to spend it.