It is now vitally important to protect the personal life

Two of my favorite movies are about the Russian Revolution. I maintain this is because the two movies happen to be just really damn good, and not because I have a particular soft spot for the events of 1917. One of these films is obviously Dr. Zhivago, although it probably ranks somewhere between 15 and 20 on my list of favorites. But the other movie is Reds, and Reds is and has been, since College, my all time favorite movie.

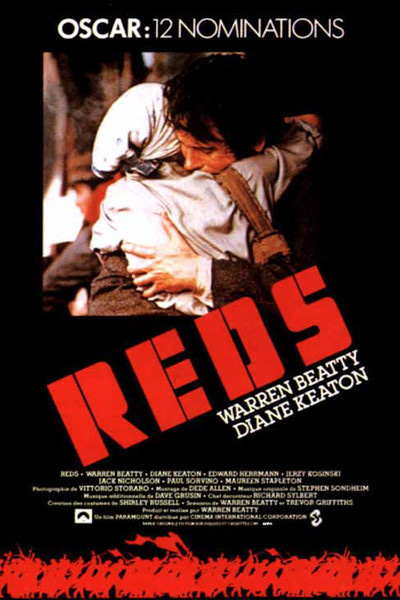

Most people I have this conversation with have never heard of Reds, much less seen it. So, perhaps a primer is in order. Released the year I was born, in 1981, Reds is about real life journalist John Reed, who, along with his partner Louise Bryant, was one of the only Americans in Russia at the time of the Russian Revolution. He wrote a book about the experience, a classic called Ten Days That Shook the World. Reed is played by Warren Beatty, who also wrote, directed, and produced the film. Diane Keaton plays Bryant, and Jack Nicholson plays their friend, playwright Eugene O’Neil. A fantastic supporting cast fleshes out various American writers, artists, and creative luminaries of that era. Reds was nominated for 12 Academy Awards and won 3, including best director for Beatty.

It’s really damn good, so, if you’re one of these people who have never seen it – go see it.

A few weeks ago I re-watched Reds, and there is a crucial scene that has been with me since. Reed has traveled to post revolutionary Russia to represent the communist party of America in the Comintern. After a series of grueling negotiations, he asks Zinoviev, a high-ranking member of the Politburo, for a train ticket so he can return to the U.S. (somewhat hard to obtain as 17 white armies were attacking the Bolsheviks from all sides at the time).

Reed: I have urgent personal considerations and responsibilities in the United States.

Zinoviev: Of what nature?

Reed: Excuse me?

Zinoviev: Of what nature?

Reed: I have a family.

Zinoviev: We all have families.

Reed: Well, I can speak only for myself. And I must see my wife, it’s very urgent. I ask only for a single place on a train.

Zinoviev: But you have a place on the train! You have a place on the train of this revolution. You have been like so many others the best revolutionaries, one of the engineers on the locomotive of the train that pulls this revolution on the tracks of historical necessity laid out for it by the party. You can’t leave us now. We can’t replace you.

Zinoviev goes on, in a tirade:

Zinoviev: What right do you have? To do what? See your wife? Last year I learned that my son was dying of typhus. I didn’t go to see my son, because I knew I was needed where I was placed by the party!

Reed: What you don’t understand is –

Zinoviev: Would you abandon this moment in your life? Would you ever get this moment again?

Reed: I am not abandoning the revolution. For the past eight weeks I have been completely –

Zinoviev: You can always go back to your private responsibilities. So can I. You can never go back to this moment in history.

It’s a compelling argument, and Zinoviev is right of course. History doesn’t walk backwards. You can’t go unring certain bells. We are always faced with whether to engage in historical moments or let them pass us by.

There is actually a similar scene in Dr. Zhivago, which is much more explicit about this. Pasha Antipov, who becomes the revolutionary Strelnikov, lectures Zhivago:

Feelings, insights, affections… it’s suddenly trivial now… The personal life is dead in Russia. History has killed it.

This is what totalitarianism does. It colonizes every aspect of public life, and when it’s done with that it moves to ensure there is no private life to compete with it. This conflict between public and private is part of what makes Dr. Zhivago such a powerful story. The poet vs. the state. How does one live a personal life when the very notion of a personal life is viewed as a subservient to the state?

Part of the reason that this time in the Russian revolution is so fascinating for me is because it was still unclear what, exactly, the revolution would become. Would it be the socialist worker utopia envisioned by Marx? Or would it be something else? In Reds, John Reed’s personal journey is precisely that unraveling of the utopian vision.

Zhivago is similar. The revolutionaries didn’t set out to erect a totalitarian state. They were not evil men; they were idealists. The problem is that they believed that history was like science, that it obeyed laws, and that Marx had discovered that those laws pointed to a worker’s socialist revolution. That is what Zinoviev meant by being pulled along the tracks of historical necessity. They believed they were merely agents of history.

And so when the worldwide workers revolution didn’t happen, when Russia, far from morphing into a socialist utopia, became mired in a bloody war and a failing economy, they took measures to convince everyone, and themselves, that the inexorable march of history would still pan out the way they said it would. They needed to believe that all that blood and sacrifice had been for something. The longer it went on, though, the longer that utopia failed to materialize, the greater the lengths they needed to travel in order to convince themselves that the dream was alive. Not only alive, but becoming a reality. And forty, fifty, sixty years later, the task was to convince everyone that this – the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics – was indeed the socialist utopia that had been promised so long ago.

All evidence to the contrary was to contradict not just the state, but the entire theory of history on which the state based its legitimacy. No wonder it turned out the way it did. The USSR came to depend on controlling thought in order maintain its original founding myth, lest the entire intellectual scaffolding of their regime be called into question. That’s why it was so important to control culture: music, art, literature, and with it, people’s personal life and inner thoughts.

Andrew Sullivan’s recent piece for New York Magazine alludes to this erosion of the personal. Here’s the widely quoted section:

One of the great achievements of free society in a stable democracy is that many people, for much of the time, need not think about politics at all. The president of a free country may dominate the news cycle many days — but he is not omnipresent — and because we live under the rule of law, we can afford to turn the news off at times. A free society means being free of those who rule over you — to do the things you care about, your passions, your pastimes, your loves — to exult in that blessed space where politics doesn’t intervene. In that sense, it seems to me, we already live in a country with markedly less freedom than we did a month ago.

Leave it to Sullivan to precisely clarify for us exactly what is at stake here. The mere existence of a personal life separate from the influence of the state is what the Soviet revolution ultimately sought to destroy. Similarly, the feeling we are all experiencing right now, the disorienting flood of fake news, alternative facts, distortions, and untruths, is precisely that erosion of the personal life for which we must all be on guard.

Turning off the news isn’t just a matter of our sanity, it’s a matter of maintaining a fee society, by which I mean the existence of a personal life free from the overbearing influence of the state. We are always concerned with our physical freedom, of course – the freedom to dissent and not be jailed, to not be arbitrarily executed as an enemy of the state, to not be sent away to a gulag. But we must also protect the very notion of a personal life. Not just the colonization of our thoughts and emotions by an unhinged President who has mastered the art of controlling news cycles with a single tweet, complemented by the all-pervasiveness social media, which we turn to for little hits of dopamine dozens of times a day, but exactly what Sullivan said: a life free from having to think about politics at all.

Yes, we must have barbecues and dinner parties and not talk about the latest executive outrage. We must hold game nights and, at least for a few hours, rid ourselves of the oppressiveness of responding to the constant stream of unreality. We must go out dancing, we must play music and sports, we must make things, do business, see art, travel, enjoy time with our kids and our families, and do all those other things of which a personal life consists. Because those are the hallmarks of a free society.