Whittling my life down to fifty books

Selling the New Hampshire farmhouse and choosing what mattered enough to cross the ocean

My shelves were down to the bones.

I had, over the course of several weeks, through initial passes with coffee and tea, then progressing to more difficult ones with wine and whiskey, finally whittled my book collection to only that which was essential.

All that I had acquired and retained in life, from New Mexico to D.C. to here in New Hampshire, was down to this. The fifty or so books that would accompany me to Barcelona.

The house, you see, was under contract.

In a few days’ time I would sign papers, load a backpack, two 49.5-pound suitcases, and my dog into the Mazda, and drive with my mom to the Boston airport, where she would drop me off before herself heading back to New Mexico.

In the previous weeks, I had driven a lifetime of possessions to the town transfer station to be dumped or to the thrift store for donation. The detritus of life, transported away. Each trash bag or cardboard box, each plastic bin asking its own questions about what was valuable in life. What was worth saving—and what not.

The rest we would abandon to the new owner or burn in the wood stove.

It was the books, though, which laid it out for me in the starkest terms: so many possessions are ultimately about identity; to shed any of them meant letting go of a certain notion about myself. To wit: am I the kind of person who actually reads Proust, or merely keeps it on his bookshelf?

To grow older is to continually question what is still left to do vs. what is time for me to give up on doing, and the same goes for books still unread. Each item was a life project that would either travel with me to Spain, or be definitively abandoned. Each a decision about what still to pursue, and what to leave behind.

I.

The decision to sell the beloved farmhouse had not come lightly, but it was a long time coming. It was at some point this Summer that the emotional Rubicon had been crossed, and the house had crossed the line from blessing to burden.

In fact, it had often been a burden. I think of my son’s birthday last year, which I spent figuring out why the well was no longer filling up the cistern in the basement. Or when three weeks of sub-zero January temps froze the sewage basin with the pump into a solid block of ice, refusing to let anything else drain.

Then there were the frequent leaks in the copper pipe, the failed water heater, mice in the pantry, strange noises, slanted floors, or the relentless, overgrown goutweed. And there was the dead sump pump one Spring melt, which led to a basement full of water—in New Hampshire, there’s always either too much water or not enough.

The breaking point came when a house-sitter reported, while we were on vacation in Cantabria, that no water was coming out of the taps. The alarm I had installed on the cistern to warn us before water levels fell too low had somehow failed. And the well line—the brand new well line—was somehow just not pulling water down the hill.

After that incident, and the attendant umpteenth round of trans-Atlantic troubleshooting, my mom and I had a heart-to-heart.

The house had been a haven to all during the pandemic. And I had used it as a workshop: learning carpentry and plumbing and electric. I’d renovated the empty garage, built a climbing wall, a sauna, learned picture framing, built furniture, raised garden beds. We’d planted fruit trees, harvested unlimited crabapples, made cider, learned food preservation.

The large property had been especially valuable when my ex-partner and her two kids and my own were all younger, and our family of five could fill its rooms. But that time was over.

At the farmhouse, I climbed to get through that breakup, and, three years later, climbed to get through another. In that house, I became a stronger climber than I ever thought I would be. It held emotional attachments far out of proportion to the number of years I’d owned it.

But the time had come to close that chapter. Another demanded my focus.

II.

“Clear the decks. Reduce. Delete. Sell,” I wrote back in January. My life had begun to feel cluttered in a way that felt almost paralyzing. The projects, tracks, processes, and goals were too much. My bandwidth was full to the point where I couldn’t concentrate.

Of all the values I was trying to live by, simplify was the one I was doing the worst at—and I resolved to do better.

In June, I closed on the Barcelona apartment. Finally, a home that was not a project. A new coat of paint, sure, and the rooms had to be furnished, appliances ordered. But aside from that, it was ready to move in. Not a space in constant demand of my attention, but rather a space to just be.

When I got to New Hampshire a few months later, I set about doing three things:

Putting the farmhouse up for sale.

Organizing to bring my dog back to Spain.

All other life projects would be on back-burner mode.

And so the trips to the transfer station and the donation pile began.

The first pass through the books in the hall outside the bedroom was fairly easy. My grandmother, who had also lived in the house several years back, had gone on something of a book-buying binge, acquiring anything she could find New England-related from local used book stores. Old histories of the White Mountains, the field guides of local authors. These were the first to go.

Next were various books on homesteading, textbook-like tomes more aspirational than useful. One on preserving food, another on square-foot gardening. A popular coffee table book about self-sufficiency on a quarter acre. By the third and fourth passes, I started to touch flesh: Robert Frost’s poems; Mark Twain’s short stories; Henry Adams’ The Education of Henry Adams.

There was no reason to get rid of such books unless a serious reckoning were underway. Soon after that, I came to books related to my graduate studies, a classical liberal arts degree that spanned the Western canon. Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, dialogues by Plato, plays by Thucydides and Euripides, Thomas Aquinas, Hegel and Kant, Marx and Engels’ The German Ideology.

I came to books that I had read and enjoyed, but which had not made an enormous impression on me. Mary Karr’s The Art of Memoir, Bukowski’s Women. Joan Didion’s South and West. And there were books that I had truly enjoyed, but did not see myself going back to, or lending.

What was left, after a particularly emotional night and several glasses of whiskey, felt definitive. Here were books, each one of which had made an important contribution at key stages in my life. Each one I could discuss at length, or explain the significance of to a stranger. Each was a book I might want to pull from the shelf to reference in future writing, or merely re-read for the pleasure of it.

The house had been slowly emptying: furniture sold on Facebook marketplace, old building materials carted to the dump, sporting goods donated to the thrift store, clothing donated or thrown away. But it was the size of the remaining book collection that marked true progress.

III.

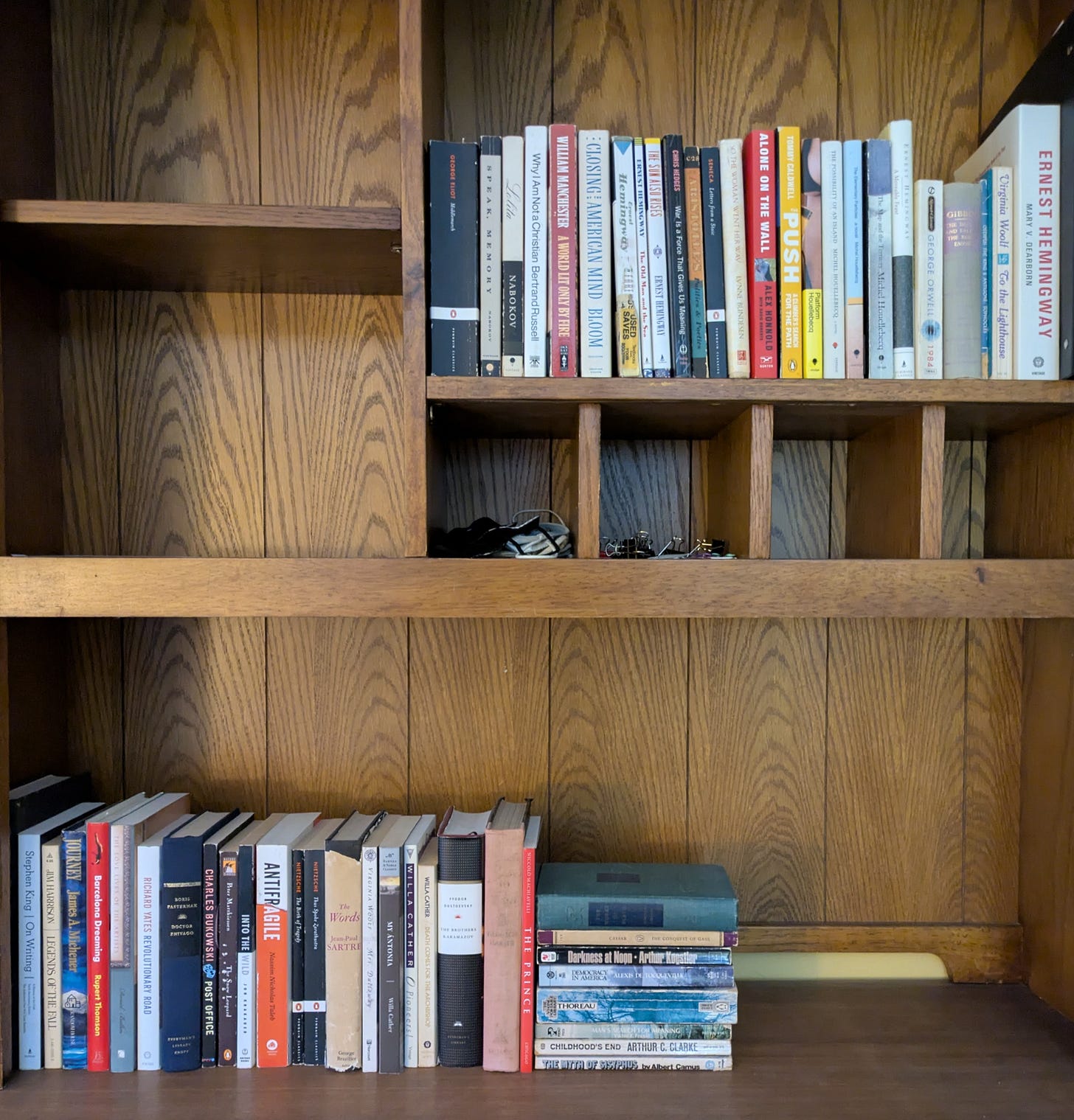

When it was nearly done, I snapped a photo:

Yet even this would be whittled just a little further once the last packing of the suitcases began, and the suitcases weighed.

But the photo is a good enough record:

George Eliot’s Middlemarch, Nabakov’s Lolita and Speak, Memory. Bertrand Russell’s Why I Am Not a Christian (I didn’t keep its opposite argument, C.S. Lewis’ Mere Christianity). Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind. I kept several books each by Hemingway, Willa Cather, and Michel Houellebecq. A copy of Aristotle’s Politics and Poetics and Seneca’s Letters from a Stoic.

I kept Virginia Woolf, George Orwell, and Stephen King’s book On Writing. I kept Jim Harrison’s Legends of the Fall, Michener’s Journey, and Yates’ Revolutionary Road. I kept Peter Matthiessen’s The Snow Leopard, Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild, and Heinrich Harrer’s Seven Years in Tibet. I kept my beautiful hardcover of Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, my tattered old hardcover of Sartre’s The Words, and some smaller softcovers of de Tocqueville, Camus, Arthur C. Clarke, Thoreau, Arthur Koestler, and Viktor Frankl. And I kept a copy of So the Woman Went Her Way, by Lynne Bundesen, my grandmother.

As many of these as I could, I packed into my carry-on. A good portion of the rest went into a small, brown rolling suitcase that turned out to feel far heavier than it looked. Some more went into the larger suitcase, along with the precious few other items I deemed worthy of travel across the ocean.

In the evenings, my mom and I poured wine, started fires in the wood stove, and burned through stacks of old papers. I couldn’t even tell you what was in all of them. Then the next day, it would be back to loading the car and driving yet another carful of accumulated possessions off the property. A lifetime carted away in weeks. Life is a constant trimming, but every once in a while, it’s burning down the forest.

That which I wanted to keep, but couldn’t take to Barcelona, went into a small trunk, which I packed into a moving pod, along with my grandfather’s reclining chair, and everything my mom wanted to take back to New Mexico, either for storage or unloading. I won’t speak for my mom—but she had her own even larger collection of books.

IV.

The last piece was Cooper.

He was a pandemic puppy, and he’d lived there at the farmhouse since my mom and I brought him home from the breeder five years ago. Technically, he had been her dog, but—and she will not dispute this—he most certainly loved me more.

We had discussed my taking him to Barcelona, and I’d been trying to organize the logistics since arriving in New Hampshire. But everything remained uncertain until the last moment.

The crucial remaining piece was the health form, which had to be stamped by the USDA itself. If only the U.S. government had not been shut down.

I scheduled Cooper’s health check-up for 30 days before travel, giving us the maximum allowed time to receive the health form back. Two weeks later, the government reopened. The Monday before my flight, we got word that the form had been approved and was in the mail. The vet could download the signed version from an online portal, but it came with an apostille stamp—and the vet and I guessed that Spain’s famous bureaucracy (or perhaps Lufthansa officials) might want the original document in hand.

But to wait any longer meant the health exam itself would be out of date past the allowed 30-day window. It was now or never.

On a Friday morning, we woke and started packing the car. The climber who was buying my house came to do a final walkthrough with my realtor. A lawyer from the title company showed up and started handing documents to me for signature. The house was empty. Cooper sat on the wood floor in the living room looking very confused.

The first winter storm of the season had dropped about six inches of snow outside just two days before, and the temperatures had dropped to sub-zero. We started one last fire in the wood stove.

By about 9:30am, it was done. I loaded Cooper into the car, into the crate I’d been training him in for months, and my mom and I said one last goodbye, stopping at the country store on the way out for a breakfast sandwich.

At the counter at Boston Logan, the Lufthansa agent checked me in, and I filled out another form to attach to Cooper’s crate that stated when he’d last been fed and had water. Per the online recommendations, I put a t-shirt I’d been wearing into the crate for something that smelled like me, and I took him for one last walk on the airport curb.

When it was time, a customs officer took us into a restricted-access hallway near check-in. He inspected and swabbed the inside of the crate and told me to take off Cooper’s collar. I put him inside, and the customs officer zip-tied the door closed. Then, he put the crate on a trolley and wheeled him away.

“That’s it?” my mom called. “He’s on his way to the airplane?”

He was. And twelve hours and one airport transfer later, he was delivered to me in Barcelona baggage claim—a little scared, certainly weary, he had a look on his face like, Why on earth did you decide to put me through that?—but five minutes later, he was out of the crate, tale wagging, and busily soaking up attention from the two customer service women at Lufthansa baggage claim.

I recovered the two other suitcases with the books, stacked everything onto a baggage cart, and, after waiting in customs for about twenty minutes, said thank you to the officer who had taken a brief look at the printed-out health form, stamped it, and waved us through.

Later that evening, I took Cooper on a long walk around my old neighborhood in Sant Antoni. He was a bit over-stimulated, but was his usual self, wagging the tail, sniffing other dogs, trotting along happily, seeking attention and pets from whoever might appear willing, and well into processing the odd turn his life had taken.

And later, after unpacking, I took a book from the shelf, lounged back on the sofa, and started reading.

Letting go of books and vinyl was almost the hardest. Then came this:

https://open.substack.com/pub/branthuddleston/p/murder-your-darlings-in-2025?r=1g9mu8&utm_medium=ios

Beautiful read. I’m going to take note of some of these books.

I’m in the process of minimizing, selling, and donating items at my parents’ home in San Diego. I can’t imagine actually emptying out this house one day. I’m not sure how many hundred of books my mom owns. That must have been such a process.

Hope your pup is enjoying Barcelona!