The Rumney Tenagi

Based on the Shinto practice of 'Misogi'—my challenge was to climb every 10a at Rumney in one day

Disclaimer: this post is especially heavy on rock climbing.

In the past, I’ve tried to write climbing-specific posts to be accessible even for those who don’t climb. In this case, I wanted to be as detailed as possible about what I did so that other climbers interested in pursuing the Rumney Tenagi can use it as a guide. As a result, I’m generally not shying away from climbing terminology.

So, this post might be a bit less accessible to non-climbers than past ones. You’ve been warned.

I. The Misogi

A ‘Misogi’ is a Japanese Shinto tradition of purification through mental and physical challenge.

Not surprisingly, the idea has been appropriated and popularized in the West, notably by author Michael Easter, which is where I heard about it. Easter wrote The Comfort Crisis, a book I read when it came out in 2021.

But it wasn’t until a month ago that I again heard Easter talk about the idea of an annual Misogi—an extreme physical challenge that you use to push the boundaries of what you think is possible.

In modern life, you can survive without being challenged. You can have food, water, shelter, etc. But by not being challenged and exploring the edges of our potential, we miss something vital about being a human. We never realize what we’re capable of—and this limits us.

Enter Misogi. It’s a circumnavigation of the edges of your potential to expand them. The idea is this: Once a year, go out into nature and do something really hard. Mimic the challenges that humans evolved to face. Explore the edges.

The idea resonates with me, not least because I’ve been known to do things like this in the past (For example, only eating food that came from my own property for a month—I basically subsisted on potatoes and vegetables and lost 15 pounds, all while climbing the hardest route of my life at the time).

As I was listening to Easter this time around I thought: why not a climbing Misogi?

II. The Rumney Tenagi: climb every 5.10a at Rumney in one day

I was in the car listening to Easter on a podcast when I thought of the idea, so I didn’t know what I was getting myself into exactly.

But I thought 5.10a would be a good grade to try something hard. What if I could climb every 10a at Rumney in one day? How many 10a’s were there even at Rumney?

When I was able to park, I brought up Mountain Project on my phone. I went to the Rumney section and sorted climbs by sport (I don’t have a trad rack), and grade. Twenty-four routes came up.1

Later, as planning progressed and my girlfriend Karen committed to supporting the challenge, I realized I’d need a name for this thing. I dubbed it the Rumney Tenagi, a riff on the idea of a Misogi.

I should say: if someone has done this before, I give full deference and credit to their accomplishment. That said, I’ve owned a home and have been climbing in Rumney since 2019. I’m reasonably connected to the community here and have mentioned this project to several locals who have been here much longer—based on these conversations, I’m reasonably confident this has never been done before, and that the Rumney Tenagi is something completely new.

Which is awesome. The challenge scratched all my itches for doing something hard, outdoors, personal to me, and in particular: meaningful.

III. Preparation and process

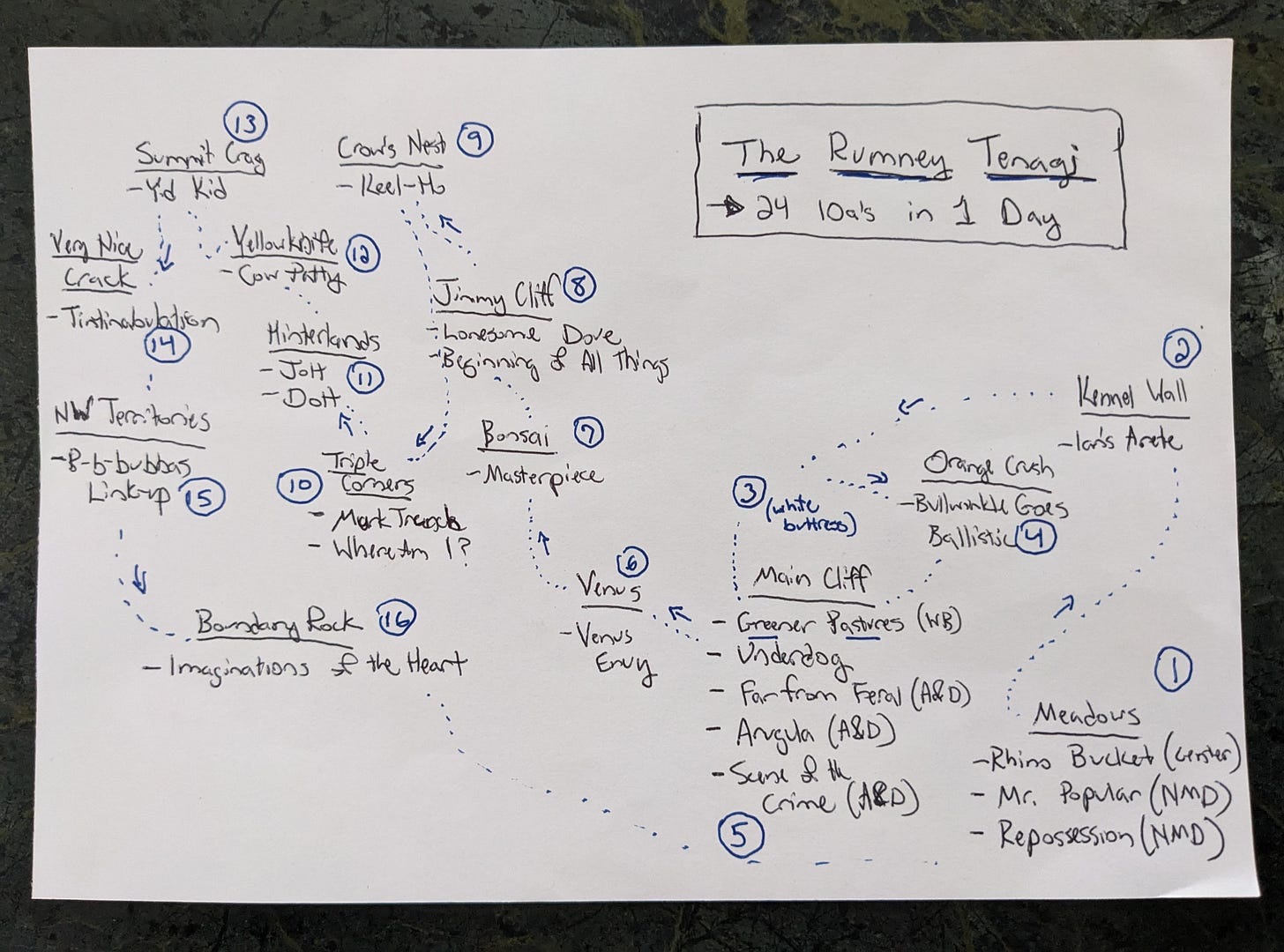

The first thing I did was map out the climbs.

Rumney’s 10a’s are spread out all over the mountain. Altogether the 24 climbs are split among 15 different cliffs (or 16 if you count Main Cliff as separate from Armed & Dangerous).

The different cliffs are about as spread out as it’s possible to be at Rumney. They start at Meadows, next to the parking lot, and they go all the way up to Crow’s Nest, Summit Crag, and include more than a dozen in between.

I needed to plan a route that would get me to all these crags reasonably efficiently. It would be a lot of climbing in one day—far, far more pitches of rock than I’d ever done in a single day—but it would also be a lot of hiking.

Not to mention: I’d never even been to many of these climbs.

We planned a day to go scout. We hiked up to the Northwest Territories, the part of Rumney most distant and highest up the mountain. I climbed B-B-Bubbas Link-up2, a long pitch up a buttress with a technical crux right off the ground and scary moves up an exposed arete at the top.

We hiked to Boundary Rock, a lichen-covered slab with a smattering of short routes I’d never been to before. Then we hiked up the terribly steep, trecherous gully to Cow Patty, a flowy 30-meter series of balancy crimps and small feet at the top of Yellowknife Buttress.

A few days after the scouting trip, we decided to give the Tenagi a dry run.

It was a hot day, and there were still a lot of unknowns. The biggest was a newish climb called Greener Pastures. The problem was that it was at the top of a three-pitch climb, so we’d have to climb two other routes just to access it. This sounded like a fun way to mix up the day, plus it meant Karen would get to actually climb some routes rather than just belay.

The day started well enough. I got through the three routes at Meadows, although I almost blew the crux of Repossession.3 When we got to the multi-pitch, I’d already climbed nine routes out of the 24.

But Greener Pastures was the wild card. I’d never been on the multi-pitch before, and multi-pitches have a way of delivering the unexpected. When I got to the top of the first pitch (Easy Street, 5.7), I saw an obvious line of bolts leading diagonally to the right. I figured that must be pitch number two. But after making the first few clips, I knew I’d made a mistake.

In the route description, it said the second pitch would be 5.5 climbing—super easy. But whatever I was on, it wasn’t 5.5. It felt more like a 5.10d or worse.

This, as the climbers say, is when we epic’d.

An epic is when a supposedly friendly day of multi-pitch climbing turns into a gigantic, draining, unexpected, possibly dangerous battle. Later, when I scrutinized the guidebook a bit more, I realized I’d likely stepped onto Cloud Atlas, a 5.11d (“Climb the first pitch of The Big Easy, then step right to a belay anchor on the ledge”). When I realized the mistake I bailed right to another climb, likely pitch two of Bourbon Street, a 5.10c, traversing down slightly, then over, then up, ultimately finishing at anchors to the left.

This zig-zagging created a huge challenge for Karen when she followed. To begin, the rope drag was enormous. Second, even on top rope, an 11d is extremely challenging. Third, the likely swing she would face if she fell on any section was pretty scary.

To top it off we could neither see nor hear each other. Even if it hadn’t been so windy, we were separated by a big bulge in the rock, and sound just doesn’t bend that way, no matter how loud you scream. She was on her own to navigate the drag, the hard moves, the swing, everything.

When Karen finally reached me, she was spent. I was also spent. And the sun had been baking both of us full-on for nearly two hours.

We continued on to the next climbs, but ultimately my body gave out at 10a number 14. It was more pitches of rock than I’d ever done in one day (14 + 2 extra from the multi-pitch). But I was still ten short of the goal.

We were out of water, running way behind on time, and I was tired enough that I didn’t feel quite in control of my limbs anymore, which meant I was tired enough to make a stupid mistake and get injured.

IV. Lessons learned from the dry-run

Of course, we’d learned some important lessons.

As with any climbing, the Tenagi would be harder in hot, sunny weather. We needed to find a cooler day, but that needed to be balanced with the fact that cooler days are also shorter days.

We needed to bring sufficient water and food. We’d run out on the dry run, and there was no intelligent way to climb that many routes while being severely dehydrated.

We had to find a more efficient way to climb Greener Pastures. The multi-pitch was out; rappelling in from the top was in. This meant re-organizing the order of routes, but it would let us skip the two extraneous pitches of climbing below.

We would have to start way earlier, basically as soon as there was daylight. We needed every hour we could get.

V. The Tenagi

On Friday, September 20th, we set the alarm for 5:45 am. By 6:20 am it was light out. By 6:41 am, we were parked at the crag and walking to the first climb.

Here’s how the day went:

Meadows

Rhino Bucket — most people hate this climb. Got me warm.

Mr. Popular — hard crux off the ground, but easy after.

Repossession — overhanging, almost blew it on the dry-run, but easy on the day.

Kennel Wall

Ian’s Arete — thoughtful, fun climbing. If the climbs at Meadows hadn’t woken me up yet, the hike up to Kennel Wall definitely did.

White Buttress (top of Armed & Dangerous)

Greener Pastures — in my opinion, one of the harder technical cruxes although it’s ultimately a very short route. On the dry run, I grabbed a draw I was so tired, but this time I sent. Eli Buzzell established this route in 2021, writing: “Feel free to accuse me of waxing poetic about a 50' dirt crawl on an already over-bolted hillside, I definitely just did. The top of the White Buttress is one of my favorite spots in the Baker River Valley, and I hope that others may find it as inspiring as I have.” I agree, the climb is nothing special but the view is one of the best at Rumney. I was glad to have this part of the Tenagi behind me early in the day.

Orange Crush4

Bullwinkle Goes Ballistic — most people use this as a warm-up for the harder routes at Orange Crush, which is my favorite crag in all of Rumney. I had been feeling good when we got to this still early in the morning, but I climbed quite ugly on the roof crux sequence here. Karen told me I was rushing, and I was. We establish our motto for the day: chill, but focus.

Main Cliff

Underdog — considered one of the Rumney classics, although I’ve climbed enough the sheen has worn off a bit. I got back into rhythm here, dancing up a climb I’ve been on at least a dozen times before.

Far from Feral — one committing roof move, then done.

Arugula, Arugula — a longer roof sequence.

Scene of the Crime — adventury, as the saying goes.

Venus Wall

Venus Envy — I on-sighted this on the dry-run day. Gave me no trouble here. We paused and ate some breakfast burritos.

Bonsai

Masterpiece — a beautiful, juggy, overhanging climb. Only pumpy if you do it wrong.

After Bonsai, we had a route decision to make. On the dry-run day, the plan took us from Bonsai past Waimea to Triple Corners. Then the idea was to go back up to Jimmy Cliff, then to Crow’s Nest, and rappel from Crow’s Nest into Northwest Territories. However, I didn’t much feel like two rappels in one day, especially from a crag I’d never been to. Instead, I decided to do Jimmy Cliff and Crow’s Nest after Bonsai, then come back down to Triple Corners and avoid the rappel by hiking from there up to Hinterlands.

Jimmy Cliff

Lonesome Dove — I’m embarrassed to say I’d never been on this climb, despite its classic status. Slab is my anti-style, and here I geared up for my first true mental challenge of the day. I on-sighted this beast, pulling scary moves, smearing, pulling out all my tricks to get through the crux sections. But I had to admit as soon as I was lowered: this was without a doubt the most beautiful slab climb I’d ever been on. Onsight.

Beginning of All Things — I agree with the route description: contrived. But it was still hard, and I was beginning to feel my body getting quite tired. Another onsight though.

Crow’s Nest

Keel-Ho — I’d never been to Crow’s Nest. It’s just far. This was a cool route, but by now it was in full-on sun. The temps were mid-70s, but every time I got into the sun everything felt harder. Another onsight.

Triple Corners

Murk Trench — blessedly short and sweet.

Where Am I? — we’d reached a milestone. I’d quit after this climb on the dry run (not having gone to Jimmy Cliff or Crow’s Nest), but here we were, after 17 pitches of climbing. Karen asked how I was feeling. My back was hurting, and so were my feet, but I still felt reasonably good. It was around 2 pm. We had seven more climbs to do, and at least 5 hours of daylight left. Chill, but focus. I could actually do this.

Hinterlands

Jolt — it’s a classic, and deservedly so, tip-toeing out a “wildly exposed” prow with all of Rumney below. Before climbing, I set an alarm for 20 minutes and we both lay down in the sun. This was the first actual rest I’d taken all day. Then the alarm chimed all too soon. We suited up and I went. 18 routes in a row.

Dolt — unpopular opinion: Sometimes I think I actually like this more than Jolt. The bottom is more engaging, and the exposed moves at the top are just as badass. 19 routes in a row.

Yellowknife Buttress

Cow Patty — we’d both climbed this on the scouting day, and I knew I liked it. But as I got on the route, everything started to crash, especially mentally. It was hard to trust the feet. It was hard to pull on the crimps. Everything felt sharp. My fingers were shredded. More than that, I was mentally exhausted from leading so much. I’d thought the limiting factor for finishing the Tenagi would be physical—but here I recognized it could be mental if I wasn’t careful. This route was the cognitive crux for me. It was covered in lichen, making the feet feel insecure, and it’s 30 meters, especially long for Rumney. It also feels very secluded up the gully. Watching me struggle with even simple route-finding, this is when Karen said she got worried about me. She thought I had the strength to keep going, but the mental challenge of leading so much could still stop me. I heard her tell me to breathe, and as she did I found a rest and gathered myself, doing as I’ve learned to do in two decades of climbing: focus on the present. One move at a time, then the next, and the next.

Summit Crag

Yid Kid — hard crux high up another steep, dirty gully on Rattlesnake. This was the last unknown of the day, another route I’d never climbed. At this point, I couldn’t tell if I was doing moves the smoothest way or the hardest way. Everything felt hard. Still, if I could get through this one, I only had routes I’d done before. Another onsight.

Very Nice Crack

Tintinabulation — I don’t love this route, and I knew that going in. But after sending Yid Kid, something flipped in my brain. I was close, and I felt it: something turned, and I went into machine mode.

Northwest Territories

B-B-Bubbas Link-up — this had scared me on the scouting day. The bottom move is crux-y, but only because I’d messed up the beta. Meanwhile, the top, an airy, exposed finish had challenged my lead head even when I was fully rested. But something happened when I started up the route this time: I found a new level in my climbing, a level I’d never experienced before. I was twenty-three pitches in, all mind, body, soul, and spirit were in sync. In high contrast to just a few routes earlier, I now felt as confident a climber as I’d ever been in my life. I was in pure flow state. Occasionally I paused and looked down at myself from above, and realized what was happening: I was floating upward. Every small shift in weight, every dance of the feet felt like grace. Every small step from nub to fin pure technique. I was on a cloud. This was it, the last one. I had found something new deep down, and I knew it, and I could see it on Karen’s face when I was lowered. Maybe it was all adreneline and endorphins, but for those ten minutes it took me to climb, it felt practically like another plane of existence.

Boundary Rock

Imaginations of the Heart — it felt like a fitting end, a coda. A brief slab, in the middle of the woods, at a crag no one ever goes to. And the name: I had imagined somthing in my heart, and here it was made real. I nearly cried when I came down. The tears sitting in my eyes—they felt like joy.

VI. Exploring Edges

Easter wrote that the Misogi is about exploring the edges of what’s possible. When you do this, it changes you:

Over the course of human evolution, we had to do hard things to survive. We were pushed out to our edges often. But in those edges, we'd learn about ourselves. We'd see we're more capable than we realize—and our edges would expand. That realization changes you.

I felt like this happened and more.

The Tenagi completely reset my conception of what my body and mind are capable of. I truly found a new level in my climbing that I didn’t know existed. What is possible now that I know it does?

Life is beautiful and exciting. Especially when lived like this.

We got back to the parking lot at 6:23pm—nearly 12 hours of near-continuous climbing and hiking.

VII. Note to the Rumney community

Of course, in speaking with friends in Rumney about this challenge, many have voiced their excitement about a new way of experiencing the crags they love and call home—my hope is that they and others will take up the challenge as a new way to climb Rumney.

As with other climbing challenges, others may quibble with the specific parameters I set for myself, but here they are:

You have to send (red point) all the routes. This is important in that it adds the actual stakes. You can’t just blow moves, hang, or ask for a take at the top of your 23rd pitch, or any others. I sent all routes on my first try (and several were on-sighted), but if I had blown a move I would have lowered and started the route again.

Start from whichever parking lot you want, but don’t use a vehicle to go between them. The time I set—11 hours, 42 minutes—is starting from the parking lot and ending at the parking lot. I didn’t feel getting in the car at any time during the challenge was appropriate because one of the beauties of Rumney is how compact the entire area is. You really can hike to every crag from any of the three parking lots.

The Rumney Tenagi is only bolted sport routes. One might arguably eliminate Greener Pastures because it’s at the top of a 3-pitch climb, but I didn’t because if you sort for the grade on Mountain Project, Greener Pastures is obviously included, and it’s bolted. My Tenagi doesn’t include trad routes, although I could easily see a very tough variation that adds the 10 additional trad routes listed on Mountain Project to the 24 sport ones.

Mountain Project grades control. Some of the routes have a different grade in the guidebook than on Mountain Project. Beginning of All Things, for example, is listed as a 10b in the guidebook. I used Mountain Project as the source of truth because the app is more accessible to more people, and also reflects more of a consensus grade than the guidebook.

I look forward to hearing about the next Rumney Tenagi—or about variations, such as adding in the trad routes, or having both you and your partner climb.

And speaking of partners: Karen was an amazing partner throughout the process and deserves huge credit. She planned food and water, was an extremely attentive belayer for 24 straight pitches, and best of all she probably believed I could do this before I believed I could do it. So many thanks go to her. 🙏

Addendum: my ranking of the best 5.10a’s at Rumney

From best to worst:

Lonesome Dove

Underdog

Jolt

Cow Patty

B-B-Bubba’s Link-up

Dolt

Masterpiece

Ian’s Arete

Arugula, Arugula

Scene of the Crime

Venus Envy

Keel-Ho

Where Am I?

Far from Feral

Yid Kid

Repossession

Beginning of All Things

Mr. Popular

Bullwinkle Goes Ballistic

Murk Trench

Greener Pastures

Rhino Bucket

Tintinabulation

Imaginations of the Heart

If you do this on Mountain Project, 26 routes come up, not 24—but two of those routes are at Gem Hunter, which is actually NOT part of Rumney. It’s located up a different road toward Stinson Lake. Sometimes small crags that are not part of larger area are grouped in with other sectors nearby. It’s just a quirk of Mountain Project.

All climbs will be linked to their Mountain Project descriptions in the section further down.

As I explain later, one of my parameters was to send every route (red point: no falls, takes, or hangs). If I blew a move or fell, my plan was to be lowered and start the route over.

Technically Bullwinkle Goes Ballistic is listed under “Below the New Wave,” but honestly that’s a weird way to list a set of climbs that is directly next to Orange Crush and serves as a warm-up to all the Orange Crush climbs. In any case, Below the New Wave should really be called Orange Crush, Right. I stand by that.

Despite the fact that I don't understand the terminology, this is some of your best writing. From the heart! You got me with the line "the tears sitting in my eyes." It's so evocative, especially since I'm your Dad!