Greetings from the Barcelona airport —

The moment I feel I’ve accomplished something on the renovation, something else happens and it feels like two steps back. Progress is even slower than you would expect, and it always seems combined with a significant jolt of stress.

Over the course of several days last week, I shoveled what I estimate to be at least 12 tons1 worth of brick and concrete debris from the back terrace of my property, into a wheelbarrow, through the narrow corridor on the ground level, out the old wood door, and up to the little park on the corner of the street. All of it I dumped into ten “Big Bags” designed to facilitate the removal of construction material from narrow spaces throughout Spain:

Later, a local building supply company came with two forklifts, lifted each of the bags onto pallets, and drove them down the hill and off toward whatever fate exists for broken concrete and brick. Presumably to a recycling center.

Ever since demolishing most of the interior walls and much of the floor on the top level, there has been a mountain of this stuff covering the only outdoor space on my property, space I wanted to reclaim if only because an outdoor terrace is the warmest place to be on my property in the wintertime—the indoors may stay nice and cool in the hot Summers, but in winter even a long string of blissfully sunny climbing days doesn’t really raise the interior temperature much.

So, I was feeling pretty good at the end.

The next day I got an email from the town hall with a very official-looking attachment that essentially puts into writing the complaint my neighbor made just before Christmas. This was after I made a hole in the side of the wall that faces his property in order to replace one of the beams (full story here).

Google is not so good at translating Catalan officialese, but the gist of the town hall document appears to be that I am being requested to rebuild the wall the way it was, or submit my plans for alteration.

Which I’ve been attempting to do for more than a month. But progress toward this elusive building permit is halting at best.

I didn’t expect much to happen during the Christmas holiday, but shortly afterward, the architect and I made another run at moving the project forward. We got an updated quote from the builder, and he wrote to the town asking for next steps—after we didn’t hear back, I tried again, and got an auto-reply: the guy was on sick leave—broken leg.

So now we need to get someone else’s attention.

Meanwhile, I’m flying to Mexico for a bit of a vacation, where I’ll meet a close friend. I’m going back to La Ventana for the third time, in Baja California Sur, to kitesurf. I’ll be very happy to transition to a different pace for a few weeks.

As I wrote two years ago:

Kitesurfing as a sport is in rhythm with both the natural world and the modern one. The natural rhythm relates to the wind: the great spots are that way because of natural factors which reliably produce wind at given times during the day and year. Trade winds, thermals, warm air meeting cool water...

These natural rhythms complement modern-day, remote office ones because they provide a predictable schedule around which it’s easy to fit whatever else you are doing for work (at least, provided that work is on a computer).

Thus, I’ll work in the morning, kite in the afternoon, eat lots of fish tacos, and enjoy some long talks with a beer at sunset, watching the sun fade over the Sea of Cortez.

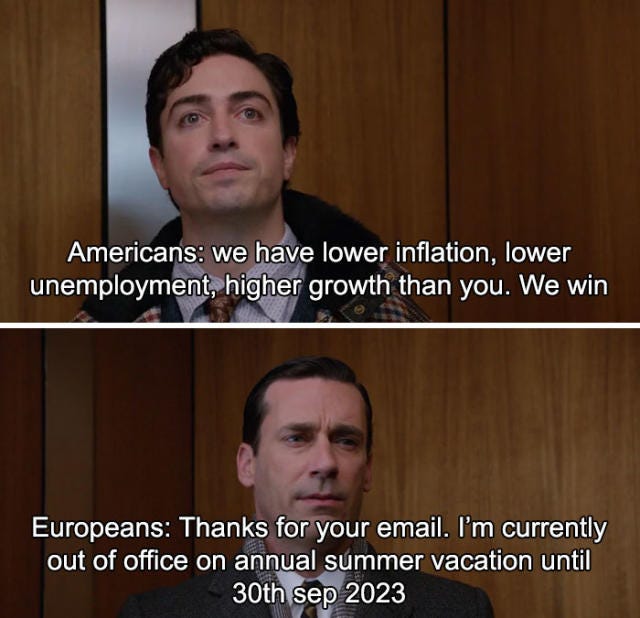

Europe vs. America, economic edition

There’s a meme I kinda love/hate where an American worker writes a European colleague. It’s the middle of the Summer and the American is writing to brag about the U.S.’ superior GDP, lower unemployment and inflation rates, and soaring stock market; then he gets an auto-reply from the European colleague: Thank you for your email. I’m currently out of office on annual summer vacation until 30th September.

As I wrote in what is now my most-read post ever by far, Europe and the U.S. just optimize for different things. If you want to build wealth or a large business, or put a dent in the universe a la Steve Jobs, I’d certainly recommend the U.S. for that. If you want to optimize for social connection, quality of life, and freedom from want, you can’t really beat Europe—especially southern Europe.

Still, I was interested in Matthew Yglesias’ piece just before the holidays: What the U.S. and Europe can learn from each other (gated, but FWIW, this is the post that finally got me to go paid), especially the question of whether all the respective strengths of the US and Europe had to be mutually exclusive.

Yglesias points out that the U.S. and Europe are generally making different choices on what to prioritize in society. But from a policy perspective, Yglesias argues that fewer of these choices require clear tradeoffs than you would think.

In other words: Europe could change a lot of things to make their economy more competitive without sacrificing the things that make their society so pro-social. Similarly, the U.S. could implement many pro-social policies that really wouldn’t hurt American economic competitiveness.

Yglesias busts a few myths in the piece, starting with the idea that total hours worked explains the difference in productivity. But that only explains about 30% of the difference in GDP per capita, according to Yglesias.

A better explanation is U.S. worker productivity per hour, which in turn can be explained in large part by energy consumption. Specifically:

European countries mostly banned fracking just when it was taking off in the United States, and Germany and other European countries have also moved to aggressively denuclearize their electrical grids. Superior European energy efficiency on the consumer side seemed like a big advantage back when the US was so heavily reliant on imported fossil fuels. But today, the US energy sector is an important driver of economic growth, while Europe has made itself energy poor and dangerously dependent on Russia.

That’s a choice Europe could easily reverse and has little to do with maintaining other pro-social policies.

The other huge driver of U.S. productivity is of course our enormously successful tech sector. Eight out of the 10 biggest companies in the world are American, and six of those are computer and software companies. Which begs the question: Why no European tech?

Many assume it’s a story about taxation, with overzealous Europeans taxing rich corporations to pay for its social safety net—but Yglesias says that’s not really correct:

According to Dealbook, there’s more venture capital in Denver than in Paris, and more in New York than in the top two European cities combined. You might think this is a tax story. Leftists love to complain about billionaires, many of whom made their money as successful startup founders, so maybe the issue is that European leftists have killed startups with punishing levels of capital taxation. Except not really — the US has higher capital taxation than Germany or Italy or Spain, and the one European country with a successful tech startup is Sweden, which has some of the highest taxes.

So what is it? According to both Yglesias and a super compelling post from Pieter Garicano (HT Tyler Cowen), the real answer to all of this is labor market regulation.

Essentially, because it’s so hard to fire people in Europe, the cost of failure for a business is orders of magnitude greater (because they still have to pay employees contracts for years, even if the business fails). This in turn stifles ambition to take large business risks.

Just check out the math here:

…the reason more capital doesn’t flow towards high-leverage ideas in Europe is because the price of failure is too high.

Coste estimates that, for a large enterprise, doing a significant restructuring in the US costs a company roughly two to four months of pay per worker. In France, that cost averages around 24 months of pay. In Germany, 30 months. In total, Coste and Coatanlem estimate restructuring costs are approximately ten times greater in Western Europe than in the United States…

Consider a simple example. Two large companies are considering whether to pursue a high risk innovation. The probability of success is estimated at one in five. Upon success they obtain profits of $100 million, and the investment costs $15 million.

One of the companies is in California, where if the innovation fails the restructuring costs $1 million. The other company is in Germany, where restructuring is 10x more expensive, it costs $10 million (a conservative estimate).

The expected value of this investment in California is a profit of $5 million. In Germany the expected value is a loss of $3 million.

Kind of simple as that, in my opinion.

Of course, I’ve been on the receiving end of this kind of restructuring. In 2019, a large healthcare company that had taken on private equity money to grow did a large restructuring after it failed to meet profitability goals. I was one of the casualties—and I was fired quite suddenly, in a matter of minutes. They gave me two months’ severance pay and wished me well.

Meanwhile, I’ve accumulated at least half a dozen anecdotes over the last year and a half about the opposite phenomenon here in Europe. Bosses here will keep terrible employees for years rather than go through the headache and paperwork of firing them—even if the employee is doing zero work and the entire rest of the team is carrying the load.

But it’s not only the dead weight of carrying useless employees—it’s that it makes no sense to hire employees in the first place:

This dynamic pushes European companies toward sticking with what they already know—not because they're more risk-averse, but because it’s the profit-maximising choice given the cost if they fail. Making big bets on new technologies is less worthwhile for big European firms. The widening innovation gap reflects the repeated effect of the structural advantage from cheaper restructuring, increased by (arguably) faster technological change.

This really does seem like a tradeoff.

My experience of suddenly being fired out of nowhere may read to a European like something out of an inhumane hyper-capitalist dystopia, just one more piece of evidence for all that’s wrong with the neo-liberal capitalist order. For me, an American, it’s just par for the course. We all go through something like it at least once in our careers. It’s a right of passage, really.

Meanwhile, to me, the boss who won’t let go of an employee, thus forcing everyone else in the organization to take up the dead weight, even though they don’t get paid anymore to do it, and even though the useless employee still pulls full salary, reads like a deeply demoralizing, morally corrosive, patently unfair system that is unhealthy at almost every level, from the individual up to the societal.

So this really is a tradeoff, and it’s one in which I think the U.S. might have the better balance, not just on an economic basis, but even on a moral one.2

Still, there are so many other ways in which the U.S. is a sick society that merely flagging its potentially more beneficial approach to labor law is cold comfort. Back to Yglesias:

America has dramatically higher rates of homicide, drug overdoses, and car accidents than Europe and moderately higher suicide rates, as well. Americans are also a lot fatter.

Add to this: we can’t build big things; we can’t fix our cities; we can’t fix our politics; gun violence has become irretrievably normalized; our public schools are failing; our military is in disrepair; debt is out of control; healthcare is unaffordable; and it’s impossible to find a plumber. We also seem to have lost sight of what is and has always been our greatest strength: immigrants who want to come build a better life (otherwise known as the American Dream).

You might think the way to solve many of those problems is by taxing the wealthy so that we can spend more money on them—but the U.S. already spends significantly more on a per capita basis than our peer nations on most of those problems3; we’re just spending it badly, and getting worse results.

In my opinion, shared by Yglesias, very few of the policy solutions to America’s problems would require it to sacrifice its economic competitiveness. Just as Europe wouldn’t have to flood its streets with concealed handguns in order to become friendlier to high-growth startups. America could get safer roads and fewer fentanyl deaths; and Europe could embrace energy abundance without sacrificing its social safety net. There is a lot we can learn from each other.

America could even start building new cities again, and build them in the mold of the old-world, pedestrian-friendly, architecturally interesting mixed-use neighborhoods that we all love so much about Europe.

Now wouldn’t that be lovely.

Judged on the carrying load of the bags.

Think about it: in order to protect the one employee from getting fired, which may or may not be due to gross negligence or bad performance (or maybe just to make the organization more profitable), all other employees must work more for the same pay. When I defend the U.S. balance on this issue, I’m the one looking out for the collective good.

To take some obvious examples: U.S. healthcare spending per capita is almost twice the average of other wealthy countries, yet we have lower life expectancy and dramatically higher rates of chronic disease. On public education, the U.S. spends significantly more per capita than our peer nations, while consistently ranking near the bottom on test scores. It goes on.

I've thought a lot about this whole conundrum and I'm fairly certain you and Yglesias have hit the nail on the head. The taxes in Europe aren't the real deal breaker, especially as California has quite high taxes yet leads the US. It's the labor laws and the approach to risk taking. Labor laws are likely the worst offender.

On the risk taking, It's purely anecdotal, but startups in Spain told me years ago that the investors would never invest in them again if they fail.... That mentality is detrimental to high growth, high risk startups like tech companies. I'm not sure how to fix investor mentalities, but it's another factor.