My language learning valley of despair

A great teacher and proper motivation go a long way.

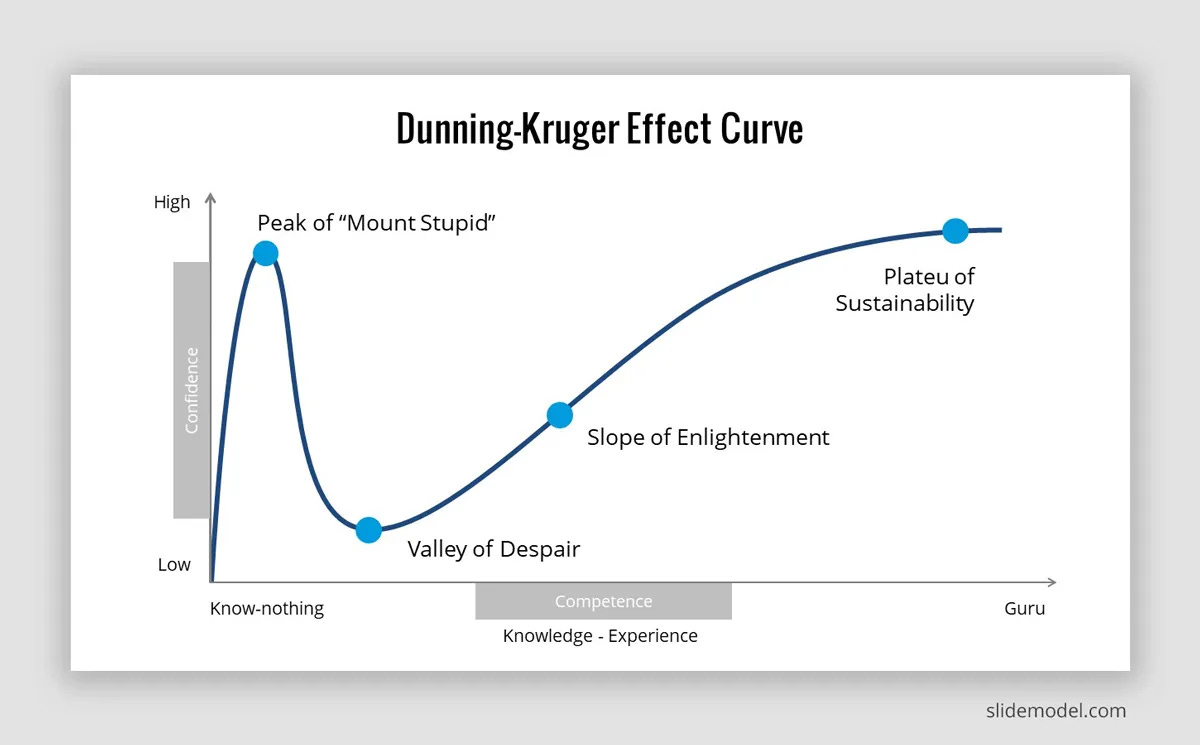

You’ve probably seen this graph before:

On the left axis is “Confidence,” and on the bottom is “Competence.”

Right when you start learning something—in my case, Spanish—your confidence tends to soar. Look! I can now order a beer and ask for the check at a restaurant!

This was 20 years ago. In school, I studied French, but sometime during College I flew to Guatemala and did two weeks of intensive Spanish. For years, that was the only Spanish I had as I traveled to various Spanish-speaking countries: Peru, Cuba, Panama, Colombia, the Dominican Republic.

Fifteen years later, I did another two weeks, this time in Ecuador. My confidence again soared. In the taxi on the way to the airport to fly back to the U.S. I held an entire conversation in Spanish! It was only 45 minutes, and I used every word I knew, but it felt like a landmark.

Then in Mexico, just before the pandemic, I did six weeks of group classes. My confidence soared further. Here was real, sustained progress. I’d even learned different past tenses this time. The last week, I’d even engaged in a small debate in class about whether deaths from this new flu in China would be worse than the opioid epidemic in the U.S.

I had reached the peak of “Mount Stupid.”

With COVID cases rising, I flew back to the U.S., hunkered down in New Hampshire, and spoke not a single word of Spanish for three years.

A problem of motivation

Some version of language proficiency has been at or near the top of my goal-setting for a while.

In 2017, while I was still living outside Washington D.C., I set a goal of getting through Unit 2 of Rosetta Stone—I failed. The next year I set a goal to do weeks of intensive classes, and that’s why I went to Ecuador. Each day after four hours of one-on-one instruction, I would slog back to my apartment completely drained. I told myself it was the altitude (Quito is at 9,350 feet above sea level).

After returning to the U.S., I didn’t speak any Spanish for a year.

In 2019, I tried to find a more sustainable pace of learning and set a goal of 10 hours/month of Skype instruction from house in Maryland. Again—fail.

Then came Mexico, the pandemic, and three years in New Hampshire, where I only Spanish I spoke in three years was introducing myself to the Honduran guys who came to help drywall the apartment renovation.

At that point, I shudder to think of how much I’d forgotten.

The problem, of course, was motivation.

I was trying to learn Spanish merely for the sake of learning Spanish. That might be enough for some people, but for me, it clearly wasn’t. It’s not that I don’t believe in learning for its own sake. In fact, as a matter of principle, I believe deeply in language learning, for all the reasons parents tell you you should.

It’s just that it turns out I’m a pretty bad student. A good test taker, yes. But in school, as my 7th-grade teacher famously told my mom during a parent-teacher conference, I was mainly skating by on good looks and charm.

Discipline is easy for me if I have a deadline. I made a good newspaper reporter. But I’ve always found language learning hard when there is no clear need to actually communicate in that language.

The tasks of memorizing vocabulary and studying grammar are not so fun. And meanwhile, language learning over a computer, either through video calls or by doing exercises online, has always felt quite draining. Besides, after the online language lesson I would always just return to my regular American life, no Spanish necessary.

This is why all my learning until now had been immersion in a foreign country. If I could combine language learning with travel, and with being in an environment where I had to speak Spanish, it worked.

But I never did manage to crack the code on how to improve my Spanish while living in the U.S. Nothing seemed to stick.

The Valley of Despair

About two months after moving to Spain, I was walking over to one of the city bike shares. A technician was there doing some maintenance on the docking station, and as I went to scan my card to unlock a bike he said something to me in Spanish.

It was just a sentence, a phrase, and it had the word “bici” in it. But as for the rest—I had no idea. It was way too fast.

It was so, so frustrating.

I’d been in group Spanish classes for two hours every morning since I arrived. I’d improved my vocabulary, learned loads of new grammar, and I’d been practicing conversation at the climbing gym, and occasionally with Spanish-speaking friends.

Yet I couldn’t understand whatever the simple sentence was this native Spanish speaker had just said to me. It was about the bikes. That’s all I knew. And of course, one didn’t need months of Spanish classes to know that much.

I was now in the Valley of Despair.

Frustrated and improvising

All told since moving to Spain, I’ve had about four months of group language classes at World Class Barcelona, which is about a seven-minute walk from my apartment.

I chose the school because it was nearby, and also because it had amazing reviews on Google (4.9 stars on more than 300 reviews).

I’ve stuck with it because of the teacher—her name is Bea, short for Beatriz, and she’s nothing short of gifted when it comes to managing a group class.

The techniques are not rocket science—drawing in every student, a variety of activites and mix of teaching methods, knowing how to pace—but Bea’s emotional intelligence when it comes to managing our frustrations and passions, navigating interpersonal, intercultural dynamics, and setting a sustainable pace of learning just outside our comfort zone has been absolutely amazing.

And her skills as a teacher are undeniable (the other day she explained a small grammatical concept in four different languages. First in Spanish, then in English, Russian, and German. She wanted to make sure each of us had understood).

I love the class, but of course I’ve gotten frustrated at times, especially when learning new grammar. Last week, for example, I had misunderstood a homework assignment, and so the written work I’d brought to class didn’t make use of the grammar Bea had been expecting. She asked me to look at my answers and improvise new sentences using the new construction—and oh did I struggle. Literally the brain neuron connections were not there yet. Every sentence out of my mouth had three or four errors, and Bea was interrupting me quite vigorously after each one.

You have to understand something about Bea: she is a 5 foot 2 Spanish ball of energy from La Mancha. Completely extroverted, every muscle on her face always alive with expression, her curiosity endless, a passion for conversation built-in to her soul. She works extremely hard, teaching for most of the day, leading tours around the city in the afternoons, and often having beers with students afterward.

But if lively conversation is involved, she’s always all in.

And every morning at 9 am for four months she has shown up and led class, even when it is Monday and we’re not there yet, on Friday when we want to check out, when we are dealing with personal issues, when we are sad or frustrated or apathetic or just plain sick of learning.

With her degreee of emotional intelligence, she knows how to manage, when to prod, when to give space, and she knows how to do it with every culture, age, and level of competency, from the 15 year old Russian soccer player, to the Ukrainian couple, literally fleeing war, to the Indian taxi driver with a grade school education, the Ph.D. retired Brazilian researcher, from the French, Dutch, and the Italians, to the Uyghur refugee. And me, the cocky American rock climber father.

So there I was, badly improvising my homework, and Bea aggressively telling me how wrong it all was, when finally I did the only thing that came to mind, which was to aggressively tell Bea back that here I was trying to improvise homework with new grammar and she’s just yelling at me—here I did a Bea impression, hombre!!! Es un error!!, because I couldn’t quite summon the actual Spanish vocabulary.

One of my classmates jumped in to offer support. She had lived in Barcelona for more than a year, and explained that she had had to adjust to the aggressive way in which Spanish locals would interrupt her in casual conversation. It had taken her some time to get accustomed (“acostumbre”) to it .

Bea didn’t skip a beat—Ah, hombre…. Russell está MUY ACOSTUMBRADO a mí, and then she turned to me with a face like, “you know it’s true,” and I had to smile and agree. It had been four months of us together nearly every morning, and I knew Bea’s style well. We’d even endured a six-hour excursion to Ikea together to buy new bed frames and mattresses, her for her new apartment in Barcelona, me for my property in Cornudella.

Tienes razón, I said, smiling—You’re right.

The entire class laughed. I laughed. We all knew Bea, and we all new she loved us, loved what she did, and was good at it. I continued improvising my homework, each sentence just slightly less wrong than the last.

4,000 words

Some days after class, I’m pretty exhausted.

Other days, I’m excited. Leaning new things keeps you feeling young, so science says, and I’m definitely feeling that.

Like, actually young.

Estimates vary, but your average 4-year-old knows about 1,500 words. I think I’m approaching around 1,000. I’m almost to a 4-year-old vocabulary level.

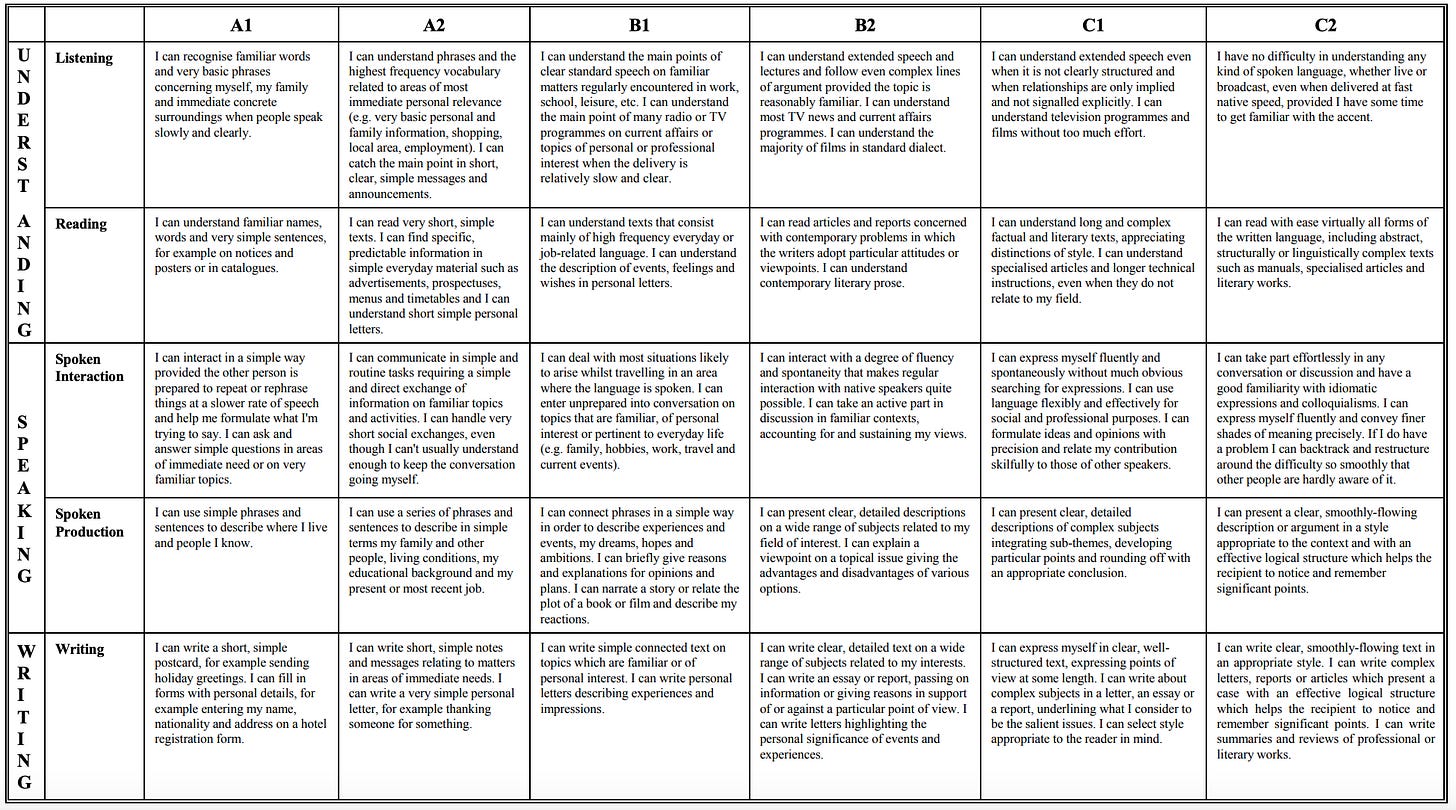

My goal is 4,000, which is the number used by the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) for Languages to describe a “B2” level of proficiency. Right now I’m technically in the “B1” level at World Class Barcelona, but the truth is I’m more advanced in some respects than others.

Here’s the whole assessment grid from CEFR (PDF here)

When it comes to reading and speaking, for example, I’m comfortably B1, but I’ve noticed that my listening is still more like A2. As it was with the maintenance guy at the bike share station.

But I want to be a solid B2 at everything. According to the CEFR chart, this will mean interacting “with a degree of fluency and spontaneity that makes regular interaction with native speakers quite possible,” meaning I will be able to take part in “discussion in familiar contexts, accounting for and sustaining my views.” I’ll also be able to “present clear, detailed descriptions on a wide range of subjects” related to my interests.

In other words, comfortably conversational.

So I continue to build my vocabulary, seek out conversation practice, watch Spanish-language shows (finding the right ones is a subject for a whole other post), and listen to Spanish-language podcasts.

Here in Barcelona, I have what I had been lacking for the past 20 years of intermittent learning: motivation.

It’s not just that I live here, although that’s a big part of it. When you are literally living in someone else’s country, I think it’s incumbant on you to learn the language, at least as much of it as is feasible whatever your circumstances.

But it’s also that that there are certain activities I care about a lot, namely climbing and the renovation project, for which I really should learn Spanish. Most people at the crags are speaking Spanish, and meanwhile, very few people in rural Catalonia speak good English (their first language is Catalan, and they learn Spanish in school).

Toward the slope of enlightenment

After the Valley of Despire on the Dunning-Krugger graph comes a slow, upward climb, where both your confidence and your knowledge steadily increase. This is where I am now: heading toward the Slope of Enlightenment.

About a month ago, I had a dream. It was about my step-brother. He and his family had decided to move from Southern California back to New Mexico, and I was there and he was telling me about it. I started asking him questions about the move, except: I was speaking to him in Spanish. There was no good reason for this in the context of the dream. My step-brother is as gringo as gringo gets, and though he does speak some Spanish, we’ve never spoken it to each other in our lives. I was just, speaking Spanish in a dream.

The next day in class I told Bea about it, and she smiled a huge grin, as she does whenever one of her students recounts a small victory. I was really learning, she said. I could toast over a beer later.

Last week, the day after I had gotten frustrated at the new grammar construction, I had a bizarre moment of zen. To my left was a Polish woman. Around the table were seated two Brazilians, an Indian, an Italian, the Ukrainian couple I’ve been in class with for months, the Uyghur, and finally a German. Together, we had been learning to express our opinions using the subjunctive, so the topics of conversation were social, cultural, and political.

Here we were in Barcelona: a class from around the globe, four different continents, eight different nationalities, discussing everything from gender equality to religious and political fantacism. And Bea, managing it all with extraordinary talent, energy, grace and understanding.

I lost track of the conversation, my mind absorbed in what a beautiful moment it was, and then I realized I’d lost track, and then remembered: I need to work more on my listening skills.

I just wrote a post about my Italian learning. I am also in B1. Being in language school with such a diverse group of people is so fun. I am definitely a social learner. Plus, all of those little interactions are great to practice (eg. hey, how was your weekend, can I buy you a coffee, etc.)

I liked the graph you shared! Sometimes I feel like it's ups and downs. It only takes one bad interaction to send me back to the Valley of Despair.

https://brenna.substack.com/p/how-i-learned-to-speak-italian-in

I love reading all of Russell's posts but this one was especially great because it tracks my experience. I will be going to Guatemala in April and am working through Pimsleur's audio classes. I'm doing pretty well. But I know from experience that I'll be flirting with the Valley of Despair once I get there.