I've been learning Spanish for 7 months—things no one told me

Plus: my process for adding 10 new words a day

There is a lot of advice on language learning out there. So much in fact I get suspicious.

I suspect the proliferation of apps, tools, programs, theories, novel approaches, and endless, endless counsel has something to do with a problem still not solved: language learning is HARD.

With so much advice out there already I never planned to write my own. Yet after seven months of group classes, combined with practice and study, I’ve learned some things I feel no one tells you at the start.

Or rather, there are things I have learned which no existing advice had prepared me for. Like many things, you have to learn by doing.

So, here’s what I know now that I didn’t know when I moved to Barcelona last Summer. Back then, I was a beginner. Now, I’ve started being able to follow and engage in conversations with native speakers, whether it’s at the crag or at a bar. It feels amazing when it’s clicking, but of course there’s still a long road ahead.

Maybe some of this will be of some small help to anyone else trying to learn.

I. Language learning will never be “easy”

Within weeks of getting here, I started seeing ads on my phone for various language-learning apps. They all promised some version of the same thing: to make it easy, or even better, effortless.

One ad promised to whisk me away for a month to a language learning retreat and return me fluent. Sure, it inspired my romantic imagination, but by then I was on to them.

It took me a moment to accept that there would be no shortcuts.

No one has discovered a way to incept new languages into your brain. It’s a fantasy. And for me, the original purveyor of this fantasy was Rosetta Stone.

Way back when, the hype around Rosetta Stone was that it would teach you to speak a new language as you learned as a child: with pictures and associations. On the screen, you see a picture of a dog, and underneath, it says perro. You see a cup, and it says taza.

What could be easier?

Except that, as detailed a few weeks ago (“My language learning valley of despair”), neither Rosetta Stone nor any other program was ever able to get me meaningfully toward fluency.

Here are some realities:

Practicing conversation as a new speaker is incredibly cognitively demanding.

Learning new grammar nearly breaks your brain the first time, every time.

Memorizing vocabulary takes consistent time and effort over a long, long time.

There simply is no substitute for doing the work.

Perhaps you already know Duolingo won’t get you to fluency, no matter how long your daily streak. But neither will any other app. Don’t fall for the promise of inception. Instead, you need a plan of attack that is sustainable and which stretches you. It will necessarily be hard.

Which brings me to point two.

II. Classes are not enough

There is a thought that if you just park yourself in daily classes for long enough, you will eventually be fluent. Unfortunately, it’s not at all true.

I’ve been taking group classes at World Class Barcelona for about seven months, with a few short breaks. The classes have been invaluable. I found a great teacher, and my classmates have grown into good friends.

Most importantly for my learning progress, being enrolled has helped me maintain momentum even when I’m feeling a bit burned out. I’ve already paid, after all, better to show up and do the work.

But classes, whether in a group or private, are not enough.

There are a few reasons. One, classes are usually focused around grammar. Yes, there is practice in listening, writing, reading, and conversation, but the primary aim of a group Spanish class scenario, in my humble opinion, is to deliver the rules of grammar.

This is great because (as least for me) grammar is the hardest thing to absorb on one’s own. I’ve tried and it SUCKS. Even when I do try to pick up new grammar solo, practicing it is hard, and there’s no one to ask questions when it gets confusing.

This is a great reason to make a group class part of your overall strategy.

But you need more. While classes can teach you the grammar, I recommend a conscious strategy outside of class to work on the other aspects of learning, including reading, writing, listening, and speaking.

Which brings me to the next point:

III. Different skill sets come at different speeds

Different aspects of language learning WILL develop unevenly.

When people say they are learning to speak another language, usually what they mean is that they want to become conversational. That’s my goal as well.

But becoming conversational involves training distinct skill sets. You need to be able to listen and understand to follow a conversation enough to engage in the first place. You need to memorize enough vocabulary to express yourself. You need to know enough grammar to string together the sentences.

And so on.

Yet the constituent parts of language learning come at different speeds for different people. If you spend too much time only doing classes, you’ll soon find some of your skills are well-developed and others not so much.

This quickly became evident about three months into my group classes.

I was picking up the grammar and had no hesitations about blurting out strings of sentences, packed with errors though they might have been. And while I found I could understand written text just fine, I also noticed I was lagging far behind in my ability to listen and understand the audio exercises.

I knew I needed to work on it.

Of course, when you’re a beginner, a lot of native conversation sounds basically like noise. And my ears are well-practiced at tuning out noise (I’m a parent after all).

It would have been all too easy to simply switch off that part of my brain every time I heard native Spanish being spoken, whether a couple at the next table, a song, or a movie I was watching with the subtitles turned on.

Instead, I had to actively work on listening, and the more I did, the more I understood.

But you have to deliberately work on it. Not just absorb.

Another area I found was lagging was simply the size of my vocabulary. Which leads to point number four:

IV. Choose a guiding direction for your vocabulary—and memorize! (My method below)

It can be very tempting to think you are further ahead than you are. Language learning is like two steps forward, one step back. You might have learned how to conjugate six different verb tenses, but unless you’ve memorized enough verbs, you’re still not going to be able to say anything.

But which words to memorize?

If you’re reading this, you’ve probably heard the advice that you don’t need to learn every word to become conversational in another language—you only have to learn the most common words.

Which is all well and good. But eventually, you need to think about what conversations you actually want to have.

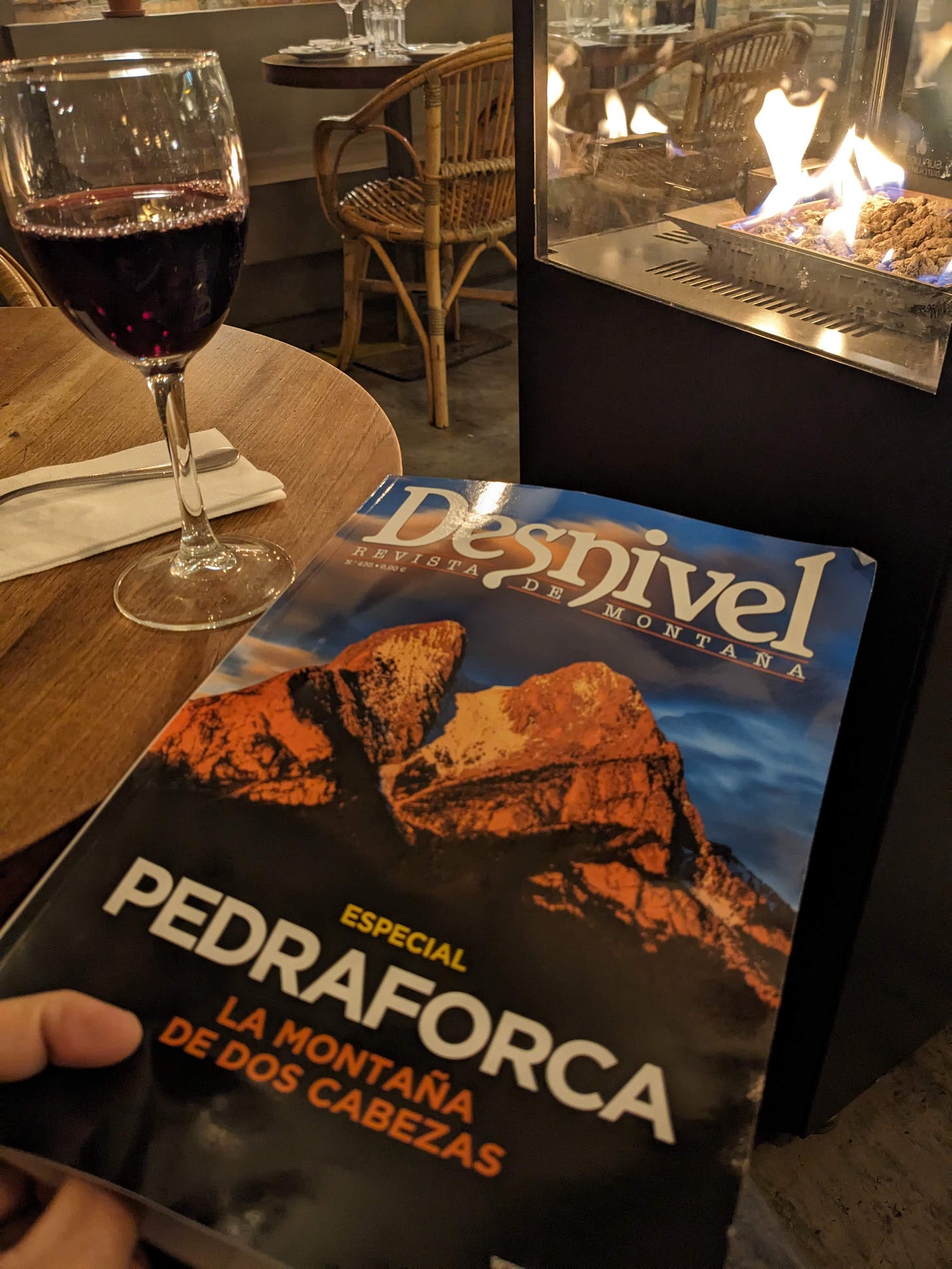

For me, it was obvious: climbing conversations (followed closely by stuff around building and renovation).

One of the first things I did after moving to Barcelona was draft a list of climbing terms I wanted to know the translations for. Climbing vocabular is an interesting case because most of the terminology is not broadly known unless you’re a climber, even to native speakers—so you can’t just ask the teacher. And feeding terms into Google translate won’t get you particularly far either. For one, there are a lot of regional differences between Spain Spanish and Latin American Spanish. Plus the terms are just too specific.

The only way to actually get Spanish climbing vocabulary is from a Spanish climber—so I sent the list to my Catalan climber friend in the U.S. and begged his help. He sent me back a list of translations, including some helpful slang. A month or two later I found a Spanish teacher from Galicia on Italki who listed climbing as one of her interests. A few conversations with her helped me flesh out my vocab.

The point is, eventually you are going to exhaust the standard subjects of a group Spanish class. And not even a list of the one or two thousand most common words will help you become conversational in the topics you actually want to discuss.

You have to choose a deliberate direction, and then go after it.

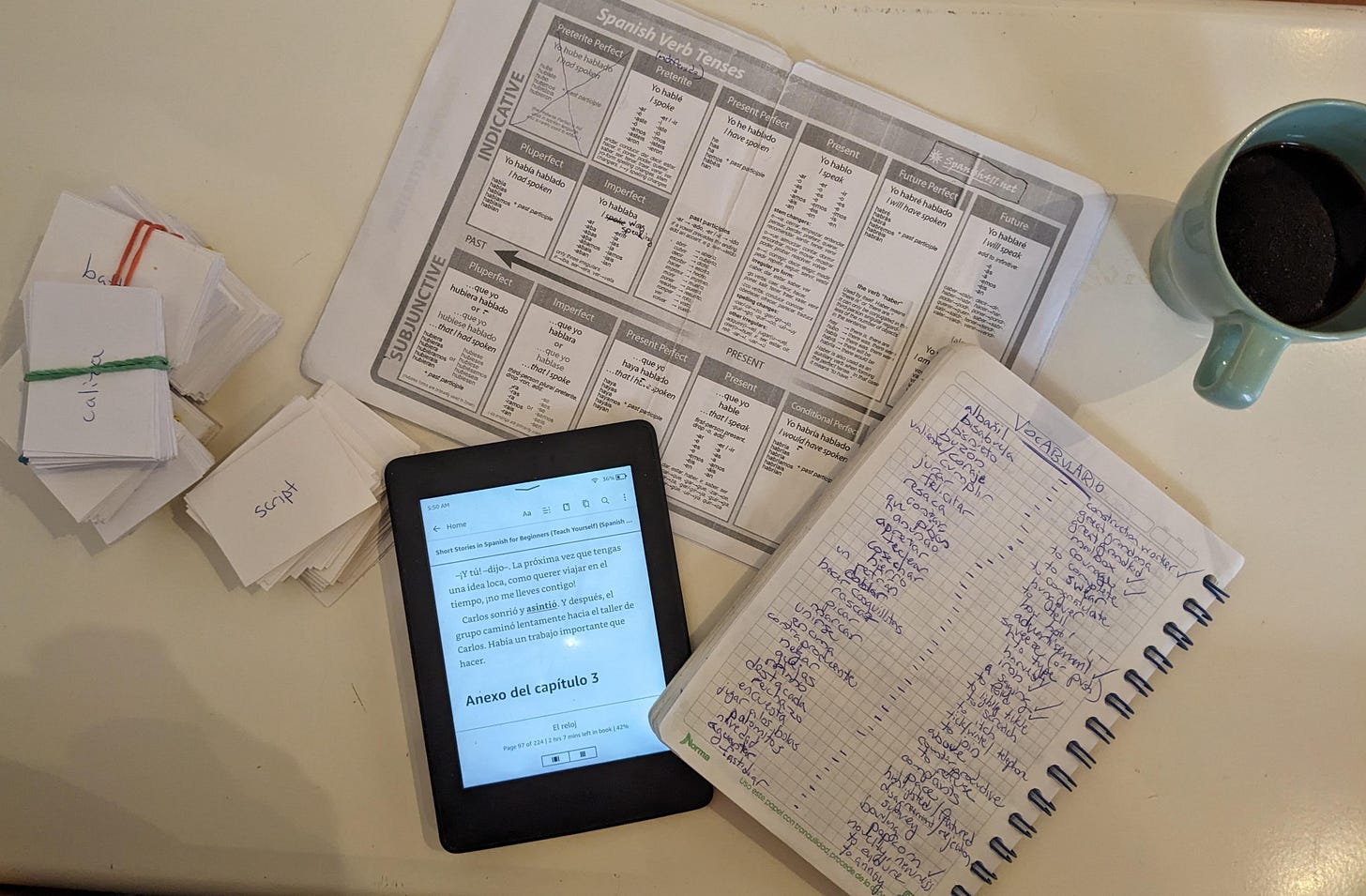

Memorization pro-tip: my memorization process is helping me add about 10 new words a day. Here’s how it goes: I use a notebook to capture words I want to learn, whether they’re from class, a recent conversation, or an article I’m reading. I draw from this list to make physical flash cards, usually 10 per day. After making the cards, I type the new words into a running conversation in ChatGPT, and ask it to give me mnemonic devices to help remember (I’ve found mnemonic devices SOOO helpful for learning fast, and asking ChatGPT to come up with them takes a huge cognitive load off my plate). Once I have the cards and the mnemonic devices, I work through the new cards a few times. Then I combine them with the cards I’m still working on from the last week or so. At any given time I have a stack of about 50-60 cards I’m solidifying. Once I know words back and forth, I take the card out of the rotation and put it into a “long-term” pile that I only go back to once every few weeks to make sure I still know them. These long-term piles are grouped into packs of 50, so it’s easy to know how many words in total I’ve added. (**P.S., one common mistake is to memorize from the Spanish side to see if you know what the word means. No! Look at the English word first, and then see if you can summon the Spanish word for what you want to say—this is the only way you’ll be able to do the same thing in conversation).

V. Immersion, yes—but curated immersion

Finally, I’m sure you’ve heard the oft-given advice that you need to fully immerse yourself in the language.

I’ll leave aside the fact that this simply isn’t possible for many people, not even for me living here in Barcelona. For one, my son doesn’t yet speak Spanish, though he’s learning. And two, none of my day job is in Spanish. So there is no “true” immersion possible for me.

That said, I’ve come to take issue with the generalized “immerse yourself” advice that you should suddenly switch all your media consumption habits to the language you’re trying to learn. No more of your favorite Netflix shows in English! From now on, only Spanish melodrama!

There are a few problems here. One is that you should still have pleasures in life—if you want to read the next Sally Rooney or Elena Ferrante novel in your native language, by all means. If you want to go see Dune 2 in English, definitely do that. You don’t need to only watch Spanish movies and shows until you’re fluent.

Another problem is that not all media is created equally. Many Spanish language shows that come up high on recommendation lists are either A., period pieces with weird time-specific vocabulary you don’t need (i.e., Catedral de Mar), or B., packed full of advanced slang that will make it extremely difficult to follow (i.e., Alpha Males).

If you really want to use TV or movies to further your language learning, I recommend something that will feel more like work and study than viewing pleasure (see point #1 above): watch a simple Pixar movie you’ve already seen a dozen times, dubbed. Since you already know the plot, you can focus on listening and you will have the subtitles for help. Then watch it again without the subtitles.

The same goes for consuming of other media, be they books, articles, or YouTube videos—you need to find the overlap between something at your level of proficiency and something you are actually interested in.

You won’t always find the perfect thing, and even if you do you’ll finish it, and then what? More curation.

The important thing to understand is this: when someone recommends you watch Cable Girls (La Chicas del Cable) for the thousandth time, remember this post and remember that you don’t have to do it. Find your own thing to watch.

My husband and I moved here from Phoenix last November and have also been taking classes at the same school, albeit the location on C/ de Sardenya! The discovery I'm making as far as learning Spanish in Barcelona is that 1) although we were exposed to a lot of Spanish in Phoenix, it's a very different regional dialect(right word?), a lot of the words are different, idioms are completely different, and the accent is completely different - so the Spanish we are used to from Phoenix has not been as much a head start as we though it would be, and 2) it has taken a while to start to hear Catalan vs Spanish, as at first I was always trying to force my brain to translate what people were saying, when often they were speaking Catalan. So Barcelona is definitely a challenging place to learn Spanish. But we're getting there - we can do what we need to do in shops and restaurants, but just not to fluency yet.

I appreciate your experience and POV. I keep hoping that once I'm living in Sicily FT, it will click. Of course, I know that's wishful thinking. My plan has simply been to use a variety of approaches. ChatGPT though... yikes. Way out of my comfort zone with that - lol!